Interesting Hydrogen Facts and History

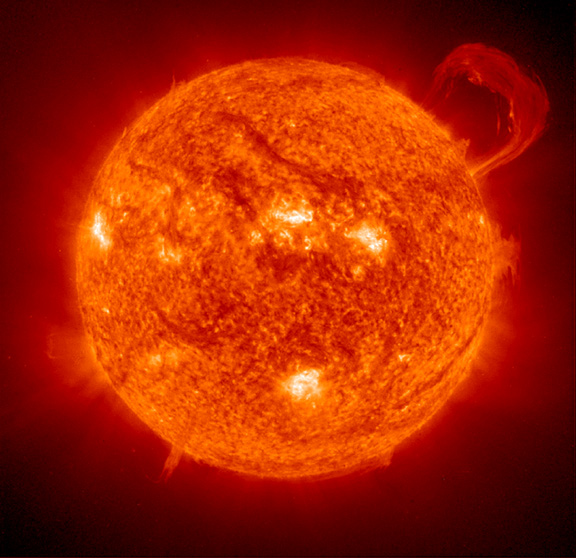

The Sun - our solar system's giant hydrogen fusion reactor.

Photo courtesy of NASA.

You could say hydrogen was a bit of an enigma. It is the most common atom, comprising about 75% of the known matter in the universe in terms of mass. If we're talking purely in terms of the number of atoms in the universe, the ratio is even more impressive, with hydrogen atoms comprising an estimated 90% of the total number of atoms. This doesn't count dark matter which is currently more theoretical than proven. Yet despite this abundance, it is rarely found in its pure natural state here on planet earth. This is mainly because pure hydrogen would just float up and away into the upper atmosphere. Therefore to capture it for uses as an alternative form of energy, it must be extracted from compounds containng hydrogen (for example water or natural gas),

As well as being the most common element, it is also the simplest, smallest and lightest element, with only one proton at its nucleus, and no neutrons. The proton is orbited by a single electron. As such it is the first member (number 1) in the periodic table of elements.

Despite being small, simple and light, hydrogen is no wimp! Most stars, like our very own sun, are powered by hydrogen fusion, whereby the nuclei of hydrogen atoms fuse together as a result of high pressure and temperature, creating a nuclear chain reaction and huge amounts of energy. Controlled fusion reactions here on Earth have been attempted but are difficult to produce in a stable and safe manner. Hydrogen fusion has been produced on a large scale on this planet, but in the form of a nuclear bomb which, by its nature, does not need to be safe and stable once it has been set off!

Although it is a gas at normal atmospheric pressure, extreme cooling can convert it to its liquid or solid state. In common with elements which are gases at room temperature, hydrogen only has a very narrow temperature range in which it becomes a liquid. At normal atmospheric pressure, hydrogen's liquid state is at a temperature of -252.8 to -259.1 degrees celsius, in other words it only has a range of 6.3 degrees celsius in its liquid state. Below -259.1 degrees celsius, hydrogen reaches its solid state, which is colorless and transparent or a snow-like conglomeration. Considering that the theoretical value of absolute zero is -273.15 degrees celsious, this only gives hydrigen a small temperature range for its solid state too, the range being about 14.05 degrees celsius.

Hydrogen has always been part of the human story - after all, its a well-known fact that it combines with oxygen to create the water which we drink and is a vital part of our human bodies. However, it wasn't until the 17th century that hydrogen was singled out as a gas, finally getting its name in 1783 from the greek words hydro (meaning water) and genes (meaning created from). The name was given by a famous French chemist called Antoine Lavoisier who, along with the Astronomer and mathematician Pierre-Simon Laplace replicated an earlier experiment by Henry Cavendish which showed that burning hydrogen in air produces water as a by-product.

For the very first hydrogen balloon flight which took place in France, also in 1783, sulphuric acid was poured over iron to create the hydrogen. Scientists of the day were playing around with an exciting thing called electicity and in 1800, the voltaic pile was invented. This was an early form of battery, comprising alternating disks of copper and zince, stacked on top of each other, each disk separated by a cloth or piece or cardboard soaked in brine. That same year, Johann Wilhelm Ritter and William Nicholson discovered that water can be split into its constituent elements of hydrogen and oxygen by passing an electrical current through the water. This process, known as electrolysis, is still often used today in production of hydrogen.

As hydrogen reacts in an explosive way when ignited in air, scientists were eager to try to use this power in a useful way. Vehicles were powered by steam at the beginning of the 19th century, but François Isaac de Rivaz envisioned another way. Between 1804 and 1806 this early pioneer of alternative energy designed a cylinder and piston engine system where hydrogen and oxygen in the cylinder would be ignited by a spark, causing an explosion which would push the piston outwards. He constructed the engine in 1807 and installed it in a carriage, using it to propel the carriage a short distance and thus inventing the first land vehicle to be powered by an internal combustion engine, long before the use of petrol (or gasoline as it's known in the USA). Later, in 1826, Samuel brown designed a hydrogen engine which he used to propel a vehicle up Shooter's Hill in London.

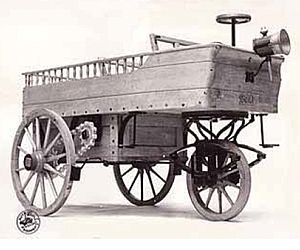

The Hippomobile - a 19th century Hydrogen Powered Car!

Fuel cells may seem to be quite modern inventions, but the first fuel cells were actually invented and produced in 1839 by William Grove. These pioneering fuel cells did not use hydrogen, but three years later, Grove did actually create the world's first hydrogen fuel cell. An early fuel cell car called the Hippomobile, made by Belgian engineer Étienne Lenoir, took a test drive from Paris to Joinville-le-Pont iin 1863. Powered by a powered by a single cylinder engine with two-stroke action, the Hippomobile travelled the 11 mile distance (18 kilometersm) in under hours, giving an average speed of 3.66 miles per hour (6 km/h),

The actual term fuel cell was coined in 1889 by the German chemist and industrialist Doctor Ludwig Mond, who lived in England from the 1860s until his death in 1909. Together with British chemist Carl Langer, Dr Mond develpoed a fuel cell with a longer life than those previously created by placing the electrolyte in a porous nonconductor,

At the beginning of the 20th century, hydrogen took off in a big way - literally - with the advent of the first rigid airship in 1900, the Zeppelin LZ1. Over the next two decades, airships grew in popularity, being used for passenger and mail transport, as well as for reconnaisance in the First world war. The tragic Hindenburg distater on 6th May 1937 effectively brought the age of hydrogen airships to an end though, when 36 people were killed as the airship crashed to the ground in a ball of fire.

This wasn't the end of hydrogen's ambitions in our skies. In the same year as the Hindenburg disaster, the first gas powered centrifugal jet engine, the Heinkel-Strahltriebwerk 1 (or HeS 1), using hydrogen as fuel, was tested on the ground. Apart from some significant burning of the engine's metal, the tests were successful, but this particular engine didn't make it into the skies. Instead, its internal parts were adjusted to use gasoline rather than hydrogen as fuel, leading eventually to the Heinkel He 178 which in August 1939 became the first turbojet aircraft to grace the skies.

The Carina Nebula.

Photo taken by NASA's Hubble Telescope.

Hydrogen had first been liquified in 1898 by James Dewar, and liquid hydrogen had been proposed as a rocket fuel as early as 1926, but it wasn't until the mid 1900s that the theories were put into actual use. A prototype reconnaissance aircraft known as the Lockheed CL-400 Suntan was developed between 1956 and 1958, under great secrecy at the time with the aim of making a successor to the U2, which was able to climb higher and fly faster than the U2 using liquid hydrogen as a propellant. The program successfully designed a concept aircraft which could travel at Mach 2.5 and reach an altitude of 30,000 m, but eventually the program was closed, due to expenses, lack of range of the aircraft, and the danger of using liquid hydrogen as a fuel for hiigh-speed jets. The work done wasn't wasted though, as it pathed the way for liquid hydrogen to be later used in rockets for the Apollo program, including the 13 Saturn V rockets which were launched between 1967 to 1973.

Another interesting epoch in the history of hydrogen, especially if you're the ghost of Colonel Gadaffi, happened in 1965, when an American company called Allis-Chalmers built the first hydrogen fuel-cell powered golf buggies.

Travelling a little bit faster, further and with an incy-wincy bit more oomph than a buggy, the Space Shuttle was a recent and impressive example of the power and ability of hydrogen. From its first launch on 12th april 1981 until the final flight on 21st July 2011, the Space shuttle used liquid hydrogen as an integral part of its man engines' thrust system to launch it into space. The shuttle carried the Hubble telescope up into earth's orbit in 1990, and from the Hubble we have been able to view some of the most impressive images of hydrogen in the universe, like the three light-year tall towers of cool hydrogen laced with dust in the Carina Nebula, one of the galaxy's largest viewed regions of star-birth.

- Login to post comments